The season of Epiphany is a time to celebrate the light breaking into our lives. Epiphany is when we recognise that God is not confined within Godself but breaks forth into creation as love. We call this the incarnation, when God continually breaks into history and does a new thing. In the southern hemisphere, this is our summer. We live, laugh, and play in the sun. In enjoying the sun, we celebrate the ways light enters our lives.

In Epiphany, we also bring our gifts and offer them to God in Christ. The best gift we can offer God is the gift of ourselves. We offer ourselves to the mystery that is God, even when we do not fully understand, because we know that, through God, we are no longer the people we used to be.

Thomas Merton describes an Epiphany surrender:

What is serious to men is often very trivial in the sight of God. What in God might appear to us as “play” is perhaps what he Himself takes most seriously. At any rate, the Lord plays and diverts Himself in the garden of His creation, and if we could let go of our own obsession with what we think is the meaning of it all, we might be able to hear His call and follow Him in His mysterious, cosmic dance. We do not have to go very far to catch echoes of that game, and of that dancing. When we are alone on a starlit night; when by chance we see the migrating birds in autumn descending on a grove of junipers to rest and eat; when we see children in a moment when they are really children; when we know love in our own hearts; or when, like the Japanese poet Bashō, we hear an old frog land in a quiet pond with a solitary splash—at such times the awakening, the turning inside out of all values, the “newness,” the emptiness and the purity of vision that make themselves evident, provide a glimpse of the cosmic dance.

For the world and time are the dance of the Lord in emptiness. The silence of the spheres is the music of a wedding feast. The more we persist in misunderstanding the phenomena of life, the more we analyse them into strange finalities and complex purposes of our own, the more we involve ourselves in sadness, absurdity, and despair. But it does not matter much, because no despair of ours can alter the reality of things, or stain the joy of the cosmic dance which is always there. Indeed, we are in the midst of it, and it is in the midst of us, for it beats in our very blood, whether we want it to or not.

Yet the fact remains that we are invited to forget ourselves on purpose, cast our awful solemnity to the winds, and join in the general dance.

[Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation (Shambhala: 2003), 302–303.]

Merton sees God at play in the sacred manuscript of nature:

· In the solitary splash of a frog in a pond, as the poet Bashō hears

· In witnessing children play

· In the silent presence of the sun, moon, and stars

He also sees God at play in the experience of love, in “micro” awakenings when our values are turned inside out, in moments of newness, and in moments of complete emptiness.

Where is God at play in your life? Where have you seen God at play in the past? What does it take for you to join the general dance and abide in God? The fact that you are here today, or reading these words, means that something has stirred within you. Do not break faith with your awakened heart.

I recall one such moment when I was arrested by God. I ministered in Johannesburg, a chaotic, beautiful, hectic city. On my way to a meeting, I was caught in a traffic jam, frustrated, with tension rising because I was late and there was much to do. When it rains, people’s driving skills seem to vanish. In the midst of this tension, Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings played on the radio. The beauty of the music overcame me. Why do I spend so many of my waking hours trapped on the outer edge of the richness of life I am living? Why do I let the centrifugal force of daily demands spin me away from the centre of love that is always holding me? And yet, I also knew that, in this moment, it was not that something more was given to me. Rather, a curtain opened, and the infinite love that has always been given to me touched me.

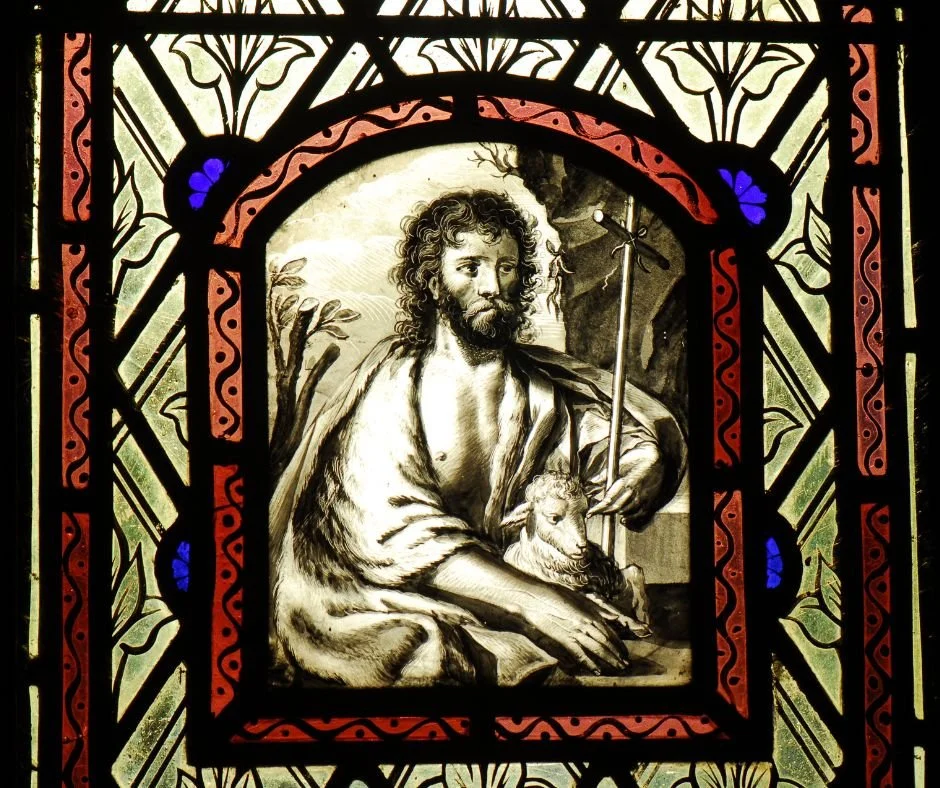

In John 1:36, the disciples of John the Baptist hear him say, “Look, there is the Lamb of God.” The Lamb of God is a metaphor for the one anointed with the Spirit—the Messiah. John describes Jesus as the one in whom the Spirit abides. These disciples then ask Jesus, “Where are you staying?” and Jesus answers, “Come and see.” Andrew stays, or “abides,” with Jesus. He experiences the awakening Merton describes when meeting Christ. Jesus asks him, “What do you want?” Andrew does not know, but he knows he wants to be as close as possible to the God he sees in Christ; he wants to abide in God. The great gift is presence.

“Abide” is dense with meaning. God abides with God, showing a dynamism where the persons of the Trinity co-inhere. The energy of love within God flows out as the Word abides with humanity (John 1:14). Jesus becomes the example of full humanity: as He abides in the Father and the Father in Him (John 14:11), so too do we abide in Jesus as branches rest in the vine (John 15:5).

Our spiritual practice is where we learn to abide. Holistic spiritual practice usually has two aspects: alone in solitude and in community.

· To your own self, be true.

· Spiritual practice is anything that helps you forget yourself.

· It requires courage, faith, and risk.

· In practice, we forget ourselves on purpose.

· We focus on love

· At times, we will feel the love of God pouring into us in abundance.

And yet, as Merton reminds us, it does not matter very much if we falter. No despair of ours can alter the reality of things. We remain in the joy of the cosmic dance, which is always there. Indeed, we are in its midst, and it is in ours, beating in our very blood, whether we want it to or not.

This is the beauty of Merton and the mystics: Do we put our faith in our ability to abide, or in the love that abides in us despite our inability? In our inability to abide, love remains, precious in our confusion and in our wayward ways.

Abiding with God we also learn to abide in each other, allowing the Christ in us to love the Christ that is in the people we share community with. As we abide in Jesus, each of us becomes the place where heaven and earth meet. Each of us is a living, breathing word of the Lord, a vision of God made manifest. It is not the perfection of our lives that makes us this place; it is our openness, our willingness to love, our acceptance of the pain of vulnerability, and our gentleness with ourselves and our mistakes that allow God to abide in us and flow through us into the world.